The Kaiser's World: What a German WWI victory would look like

Jul 27, 2020 10:38:10 GMT

lordroel, Carolus Orlandus, and 1 more like this

Post by EwellHolmes on Jul 27, 2020 10:38:10 GMT

In early 1918, the German Empire would launch its last series of offensives on the Western Front, although all are collectively referred to in the singular under the umbrella term of the "Spring Offensive". The German effort was the beneficiary of the collapse of the Russians, allowing the German Army to focus on a singular front for the first time in the war, as well as the refinement of tactics via four years of brutal wartime experimentation and learning. Driven by the very real calculation that the mass arrival of American troops would make victory impossible, the Germans would attempt their last ditch attacks starting in March and would not cease until June, by which point they were exhausted and the AEF was beginning to become increasingly noticeable along the front.

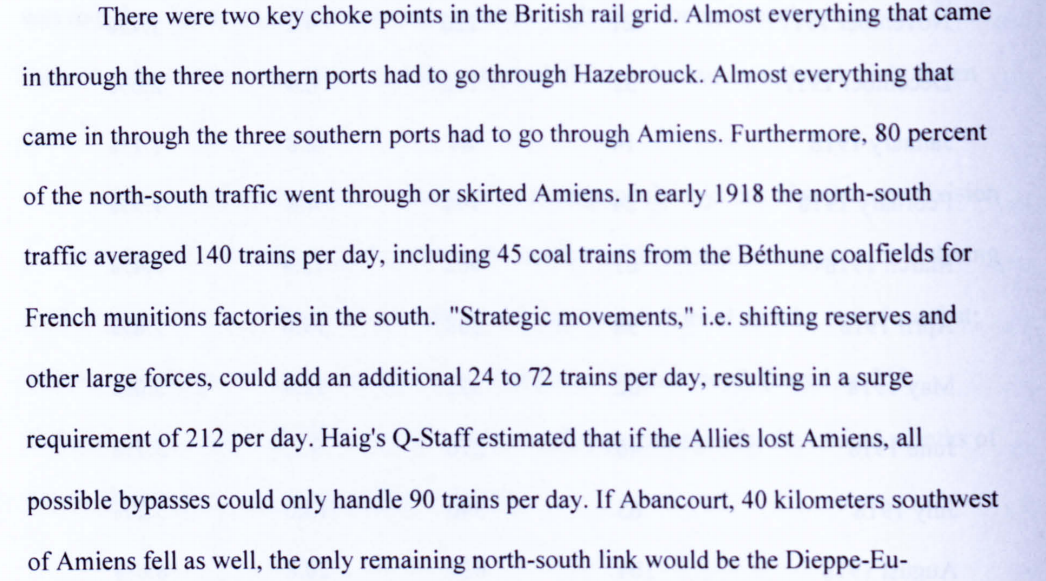

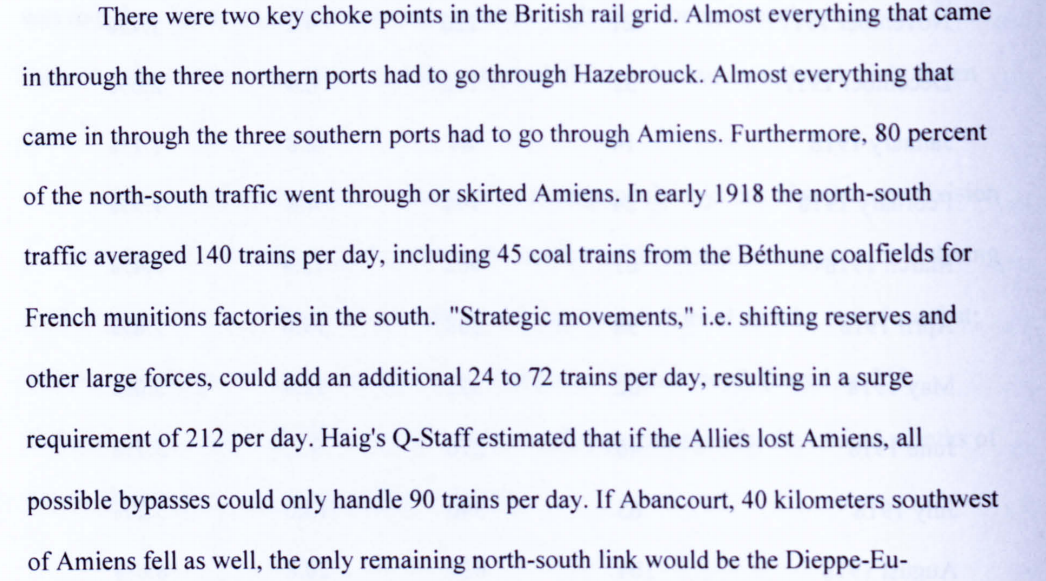

Although the Germans ultimately failed, they did come extremely close to victory. Amiens, one of the two critical railway hubs for the BEF's logistics, had the German Army come within three miles of seizing it while its aforementioned railway was subjected to harassment fire that did effect its operations. Indeed, as David T. Zabecki notes in his The German Offensives of 1918, considered one of the premier accounts of the eponymous attacks, the threat was very real and the BEF was in desperate straits:

Indeed, as late as June 9th of 1918, as the last major German attack-directed at Paris-was developing, Lord Milner would write to Lloyd George that:

So how could the Germans come to win? Zabecki presents one such scenario on Pages 139-141, although there are many that could be inserted instead:

So let's say the Germans do this, allowing them to close the remaining mileage to Amiens, eliminating 50% of the BEF's logistics immediately. Combined with the existing disruption to the Hazebrouck route, this allows Operation Georgette to take Hazebrouck; the BEF is thus compelled to destroy 90% of its equipment and retreat off the continent in a "1918 Dunkirk" that leaves the British out, at a minimum, for a year as it will take time to rebuild their equipment. Perhaps more pressing for the United Kingdom is that German control of the Channel ports will provide the Germans with the means of finally starving England into submission:

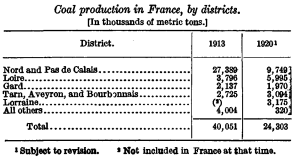

The situation will be disaster for the French as well, who will now have their right flank open with the evacuation of the British, and are also now greatly outnumbered; the French Army as a result will be compelled to surrender most, if not all, of Northern France and Paris will likely come under siege. Perhaps just as disastrous is the loss of the Bethune coal mines, which fed the Parisian war industries which constituted 70% of overall French output. In short, the Germans will have inflicted a one-two punch that forces the Entente to the table. What does the peace that comes after look like?

Adam Tooze in his famous The Wages of Destruction gives us an idea:

John Keegan in his own The First World War also explains German claims in France in better detail:

The importance of this war goal cannot be overstated; the portion of Lorraine the Germans sought is called Briey Longwy. Of the 21.57 million tons of iron ore produced in 1913 by France, 90% was mined in Briey Longwy according to Abraham Berglund, "The Iron-Ore Problem of Lorraine," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 33, No. 3 (May, 1919), pp. 531-554. Germany had occupied this area as early as August 4, 1914 and thus would have a pretty firm claim on the area. Likewise, as noted by Tooze, the portion of Calais the Germans sought to strip from France would also remove the aforementioned Bethune coal mines from the control of Paris. In short, France would be rendered incapable of being a peer competitor of Germany and, indeed, barely fit to hold the title of regional power.

As a side note, outside of their acquisitions on the continent, Britain and France would both be compelled to return occupied German colonies in Africa. Belgium would be forced to cede the Congo to Germany, but would in exchange receive the area around Calais which is also known as French Flanders. France would be forced to cede Dahomey, French Congo, Ubangi-Shari, and perhaps Madgascar as well as portions of French Chad. Britain would not lose anything and it is possible that Germany might cede German Southwest Afrika, in an effort to court the Dominion of South Africa.

Moving to the East, in which the Germans were seeking to model in their own image via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, we again turn to Adam Tooze. This time we cite from The Deluge, his coverage of 1916 to roughly 1931:

On the whole, we can thus conclude the 20th Century would be one dominated by Imperial Germany as the chief superpower. As for the United States, they will be a close second, as indicated by Tooze and the expectations of contemporary Germans.

In particular for the United States, German victory could have some unexpected ramifications. In 1919, there was a major war scare with Mexico over attacks on American diplomats and a threat to nationalize the oil industry (largely owned by Americans). This came at the worst possible point as America was already in the throes of the First Red Scare and was compounded by Congress, which at this time also produced documentation of Pro-German and Pro-Bolshevik actions within Mexico, inflaming the crisis. In a situation where Imperial Germany has won, these fears would likely be heightened, as would fears of Bolshevism (more on this later!). This could have serious effects, best exemplified by this statement before Congress by Congressman J.W. Taylor of Tennessee:

Taylor was not alone in his sentiments, as these feelings were the culmination of a decade of frustration and anger with Mexico, stretching back into the height of that country's Revolution. To quote from "An Enemy Closer to Us than Any European Power": The Impact of Mexico on Texan Public Opinion before World War I by Patrick L. Cox, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Jul., 2001, Vol. 105, No. 1 (Jul., 2001), pp. 40-80:

Arizona's Senate delegation also at this time advocated for the annexation of Baja California, at the least. For more information, see:

Woodrow Wilson and the Mexican Interventionist Movement of 1919

1919: William Jenkins, Robert Lansing, and the Mexican Interlude

Tempest in a Teapot? The Mexican-United States Intervention Crisis of 1919

Moving back to Europe once again and explaining my earlier statement of why Anti-Bolshevism being worse here, we must recall that even in victory, the Red Tide threatened to consume much of Europe. Italy had the Biennio Rosso, two years of unrest and violence rising to near Civil War levels; can one not envision at least a serious Bolshevik attempt to completely take over following a disastrous defeat after years of massive bloodshed? How about France, which had already seen massive unrest in 1917 and in 1920 had far left elements show a strong showing in the elections; they too could be radicalized via the defeat of France the same way German Bolsheviks were.

It may perhaps be surprising, but even Britain was not immune to this Red threat, herself very nearly succumbing to an attempted Revolution. To quote from The Russian Revolution and the British working class:

As the article goes on to note, 1919 was the worst year in that critical time period for Britain, with over 2.59 million workers involved in 1,352 work stoppages and over 34,000 working days lost as a result. The article is also backed up by 1919: Britain on the Brink of Revolution:

On the whole, there is a serious risk that many of the now defeated Entente powers could slip into Bolshevik control or, at the very least, civil war initiated by the same. German bayonets would probably allow Anti-Communist forces to prevail in France and Italy, but Britain, given its position as an island, holds a very real risk indeed. Thus, it is entirely possible that as Germany and America reach for their Imperial goals, the British Empire could collapse as the Home Island falls to Revolution. That this would open up opportunities for other players, such as the United States, Germany, the Ottomans, etc cannot be ignored. Although his comments are on a different scenario (America staying neutral in 1917), H.L. Mencken provides some insights in this regard that I feel could prove useful in our speculations:

Baltimore Evening Sun, Nov. 11, 1931, "A Bad Guess" by H. L. Mencken:

On a final note, with the Red Scare being so much worse in 1919 and likely large numbers of IOTL Fascist Italians running about given the disorder in Italy, I wouldn't be surprised if the United States ended up becoming Fascist in this ATL. Henry Ford came close to winning a Senate seat in 1918 for Michigan and could serve as the Salazar or Hindenburg for such a regime later on, with men like Father Coughlin as the Goebbels of the regime, Huey Long as the Hitler, and Ezra Pound as the Bormann, etc.

Although the Germans ultimately failed, they did come extremely close to victory. Amiens, one of the two critical railway hubs for the BEF's logistics, had the German Army come within three miles of seizing it while its aforementioned railway was subjected to harassment fire that did effect its operations. Indeed, as David T. Zabecki notes in his The German Offensives of 1918, considered one of the premier accounts of the eponymous attacks, the threat was very real and the BEF was in desperate straits:

Indeed, as late as June 9th of 1918, as the last major German attack-directed at Paris-was developing, Lord Milner would write to Lloyd George that:

"We must be prepared for France and Italy both being beaten to their knees. In that case the German-Austro-Turks-Bulgar bloc will be master of all Europe and Northern and Central Asia up to the point at which Japan steps in to bar the way, if she does step in. In any case it is clear that, unless the remaining free peoples of the world, America, this country and the Dominions, are knit together in the closest conceivable alliance and prepared for the maximum of sacrifice, the Central Bloc will control not only Europe and most of Asia but the whole world."

So how could the Germans come to win? Zabecki presents one such scenario on Pages 139-141, although there are many that could be inserted instead:

After 1916 submarines, mines, coastal artillery, and naval aviation were the German Navy's only effective weapons in the West. Had these assets been directed against the BEF's lines of communications (LOCs) in the Channel in coordination with a focused attack ground attack against the BEF's rail network, the British might well have been forced to withdraw from the Continent. The German submarine threat against their sea LOCs was a constant concern to the British, and one of the objectives behind the bloody battle of Passchendaele was to clear the Channel coast of the U-boat bases.

German mines in the Channel could have been delivered by air or by submarine. The Navy's Freidreichshafen bomber was capable of carrying and dropping 750-kilogram naval mines. One such mine, in fact, sank a Russian destroyer during the Baltic Islands operation. Submarines were the other way to lay mines, with the UC-class boats specifically designed as minelayers. Most of the UC-boats carried 18 mines. The U-class boats were fleet submarines that fired torpedoes; but in 1918 the Germans launched ten of the Project 45 fleet U-boats that could lay 42 mines through their torpedo tubes and carry an additional 32 mines in deck containers.

By the start of 1918, the Germans had 42 operational fleet U-boats; 66 operational coastal U-boats (UB-class); and 33 operational UC-class minelayers. During 1918 they built an additional 25 U-class (including the Project 45 boats); 47 UB-class; and 16 UC-class. The British, of course, had the Channel heavily mined, which increased the hazards of any U-boat operations. Mines caused 27 percent of the total German U-boat losses. Of the total of 53 UC type U-boats the Germans lost during the war, 19 were lost to mines. The Germans, nonetheless, had a capability to lay mines in the Channel and at least disrupt that leg of the BEF's LOCs. On 14 February 1918, the German Navy did launch one major and largely successful surface raid against British defenses between Dover and Calais. The Heinecke Torpedo Boat Flotilla sunk 28 British picket ships and other vessels, including an older cruiser. That raid, however, was never followed up. Nor had it been coordinated with OHL, rather it had been launched at the request of the Naval Corps in Flanders. Even after the failure of Operation MICHAEL in March 1918, General Ferdinand Foch still thought that increased submarine operations in the Channel posed a serious threat to cutting off the BEF.

Finally, German naval artillery could have been turned against the BEF's channel ports. The three so-called Paris Guns (Wilhelmgeschütze) were actually manned by naval crews. With a maximum range of 127 kilometers, they had the reach to hit the BEF's three primary northern Channel ports (Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk) and even Dover, if the guns had been positioned in the Fourth Army sector. But between 16 and 30 March 1918, during 140 Operation MICHAEL, they did not fire in support of the attacking Seventeenth, Second, or Eighteenth Armies. Rather, the guns were positioned in the Seventh Army sector, delivering pointless terrorizing fire against Paris.

At least two German coastal batteries in Flanders were capable of hitting Dunkirk and could have fired in support of ground forces during Operation GEORGETTE. But Batterie Deutschland (four 3 80mm guns) never fired against land targets, and Batterie Pommern (one 380mm gun) delivered only occasional fire against Dunkirk and the major British base at Poperinghe. A third battery, Batterie Tirpitz (four 280mm guns), had the range to hit targets in the northern quarter of the Ypres Salient, but it too never fired in support of ground operations.

German mines in the Channel could have been delivered by air or by submarine. The Navy's Freidreichshafen bomber was capable of carrying and dropping 750-kilogram naval mines. One such mine, in fact, sank a Russian destroyer during the Baltic Islands operation. Submarines were the other way to lay mines, with the UC-class boats specifically designed as minelayers. Most of the UC-boats carried 18 mines. The U-class boats were fleet submarines that fired torpedoes; but in 1918 the Germans launched ten of the Project 45 fleet U-boats that could lay 42 mines through their torpedo tubes and carry an additional 32 mines in deck containers.

By the start of 1918, the Germans had 42 operational fleet U-boats; 66 operational coastal U-boats (UB-class); and 33 operational UC-class minelayers. During 1918 they built an additional 25 U-class (including the Project 45 boats); 47 UB-class; and 16 UC-class. The British, of course, had the Channel heavily mined, which increased the hazards of any U-boat operations. Mines caused 27 percent of the total German U-boat losses. Of the total of 53 UC type U-boats the Germans lost during the war, 19 were lost to mines. The Germans, nonetheless, had a capability to lay mines in the Channel and at least disrupt that leg of the BEF's LOCs. On 14 February 1918, the German Navy did launch one major and largely successful surface raid against British defenses between Dover and Calais. The Heinecke Torpedo Boat Flotilla sunk 28 British picket ships and other vessels, including an older cruiser. That raid, however, was never followed up. Nor had it been coordinated with OHL, rather it had been launched at the request of the Naval Corps in Flanders. Even after the failure of Operation MICHAEL in March 1918, General Ferdinand Foch still thought that increased submarine operations in the Channel posed a serious threat to cutting off the BEF.

Finally, German naval artillery could have been turned against the BEF's channel ports. The three so-called Paris Guns (Wilhelmgeschütze) were actually manned by naval crews. With a maximum range of 127 kilometers, they had the reach to hit the BEF's three primary northern Channel ports (Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk) and even Dover, if the guns had been positioned in the Fourth Army sector. But between 16 and 30 March 1918, during 140 Operation MICHAEL, they did not fire in support of the attacking Seventeenth, Second, or Eighteenth Armies. Rather, the guns were positioned in the Seventh Army sector, delivering pointless terrorizing fire against Paris.

At least two German coastal batteries in Flanders were capable of hitting Dunkirk and could have fired in support of ground forces during Operation GEORGETTE. But Batterie Deutschland (four 3 80mm guns) never fired against land targets, and Batterie Pommern (one 380mm gun) delivered only occasional fire against Dunkirk and the major British base at Poperinghe. A third battery, Batterie Tirpitz (four 280mm guns), had the range to hit targets in the northern quarter of the Ypres Salient, but it too never fired in support of ground operations.

So let's say the Germans do this, allowing them to close the remaining mileage to Amiens, eliminating 50% of the BEF's logistics immediately. Combined with the existing disruption to the Hazebrouck route, this allows Operation Georgette to take Hazebrouck; the BEF is thus compelled to destroy 90% of its equipment and retreat off the continent in a "1918 Dunkirk" that leaves the British out, at a minimum, for a year as it will take time to rebuild their equipment. Perhaps more pressing for the United Kingdom is that German control of the Channel ports will provide the Germans with the means of finally starving England into submission:

Submarine warfare that threatened the London approaches increased the pressure, and efforts to divert shipping to west coast ports were only partially successful. London was a lighterage port and could not be converted easily to massive rail use. Attempts to supersede a city infrastructure designed to live off of riverside supply lines with inland shipments by rail were likely to throw distribution networks into chaos. One effort to divert cargoes to Plymouth underscored the futility of feeding the entire London basin via rail deliveries from other ports. Out of 27,000 tons off-loaded, only 7,000 made their way to the capital, and there were railroad backups while they did so. It took approximately three weeks to unload the ships in Plymouth, whereas the job would have been done in seven in London.[15]

The situation will be disaster for the French as well, who will now have their right flank open with the evacuation of the British, and are also now greatly outnumbered; the French Army as a result will be compelled to surrender most, if not all, of Northern France and Paris will likely come under siege. Perhaps just as disastrous is the loss of the Bethune coal mines, which fed the Parisian war industries which constituted 70% of overall French output. In short, the Germans will have inflicted a one-two punch that forces the Entente to the table. What does the peace that comes after look like?

Adam Tooze in his famous The Wages of Destruction gives us an idea:

In the twentieth century the future of the balance of power in Europe would be defined in large part by the relationship of the competing interests in Europe to the United States. Stresemann certainly did not underestimate either military force or the popular will as factors in power politics. In the dreadnought race, Stresemann was a consistent advocate of the Imperial fleet, in the hope that Germany might one day rival the British in backing its overseas trade with naval power. After 1914 he was amongst the Reichstag's most aggressive advocates of all-out U-boat war. But even in his most annexationist moment, Stresemann was above all motivated by an economic logic centred on the United States.12 The expansion of German territory to include Belgium, the French coastline to Calais, Morocco and extensive territory in the East was 'necessary' to secure for Germany an adequate platform for competition with America. No economy without a secure market of at least 150 million customers could hope to compete with the economies of scale that Stresemann had witnessed first hand in the industrial heartlands of the United States.

John Keegan in his own The First World War also explains German claims in France in better detail:

Despite the near-desperate situation at the front, the Kaiser, government and high command all agreed, on 3 July, that, to complement the acquisition of territories in the east, the annexation of Luxembourg and the French iron and coal fields in Lorraine were the necessary and minimum terms for concluding the war in the west.

As a side note, outside of their acquisitions on the continent, Britain and France would both be compelled to return occupied German colonies in Africa. Belgium would be forced to cede the Congo to Germany, but would in exchange receive the area around Calais which is also known as French Flanders. France would be forced to cede Dahomey, French Congo, Ubangi-Shari, and perhaps Madgascar as well as portions of French Chad. Britain would not lose anything and it is possible that Germany might cede German Southwest Afrika, in an effort to court the Dominion of South Africa.

Moving to the East, in which the Germans were seeking to model in their own image via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, we again turn to Adam Tooze. This time we cite from The Deluge, his coverage of 1916 to roughly 1931:

If the British had been able to see inside Ludendorff’s staff offices in the summer of 1918, they would have found ample fuel to feed their fears. Up to the end of June, Chancellor Hertling was able to hold the line established in mid-May, blocking military advances in the East. This position was communicated to the Bolsheviks, enabling them to concentrate their trusty Latvian regiments, fighting as they believed for their independence, against the Czechs, who were fighting for theirs.13 But the equilibrium in Germany was precarious. In late June a memo prepared by Ludendorff’s staff, on ‘The Aims of German Policy’ (Ziele der deutschen Politik), made clear the extent to which German military policy had radicalized since Brest. Ludendorff’s aim was no longer merely to exercise hegemony over the periphery of the former Tsarist Empire, leaving the Bolsheviks in the rump of Russia to their own ruinous devices. In a mirror image of Lloyd George’s vision of a democratic bastion in Russia, Ludendorff aimed to reconstruct an integral Russian state that thanks to its conservative political make-up could be counted on as a ‘reliable friend and ally . . . that not only poses no danger for Germany’s political future, but which, as far as possible, is politically, militarily and economically dependent on Germany, and provides Germany with a source of economic strength’.14 The peripheral states of Finland, the Baltic, Poland and Georgia would remain under German protection. The return of Ukraine to Moscow would be bartered against German economic control over Russia as a whole. Harnessed to the Reich, Russia would provide the means for Germany to exert its domination throughout Eurasia. It would provide the hinterland for an economically self-sufficient, politically authoritarian ‘world state structure’ (Weltstaatengebilde), capable of competing head on with the ‘Pan-American bloc’ (panamerikanischen Block) and the British Empire.15

On the whole, we can thus conclude the 20th Century would be one dominated by Imperial Germany as the chief superpower. As for the United States, they will be a close second, as indicated by Tooze and the expectations of contemporary Germans.

In particular for the United States, German victory could have some unexpected ramifications. In 1919, there was a major war scare with Mexico over attacks on American diplomats and a threat to nationalize the oil industry (largely owned by Americans). This came at the worst possible point as America was already in the throes of the First Red Scare and was compounded by Congress, which at this time also produced documentation of Pro-German and Pro-Bolshevik actions within Mexico, inflaming the crisis. In a situation where Imperial Germany has won, these fears would likely be heightened, as would fears of Bolshevism (more on this later!). This could have serious effects, best exemplified by this statement before Congress by Congressman J.W. Taylor of Tennessee:

"If I had my way about it, Uncle Sam would immediately send a company of civil engineers into Mexico, backed by sufficient military forces, with instructions to draw a parallel line to and about 100 miles south of the Rio Grande, and we would...annex this territory as indemnity for past depredations . . and if this reminder should not have the desired effect I would continue to move the line southward until the Mexican government was crowded off [the] North America."

The Wilson administration and the military again blamed the conflict on Villa. Governor Ferguson expressed the feelings of many when he advocated United States intervention in Mexico to "assume control of that unfortunate country." J. S. M. McKamey, a banker in the South Texas community of Gregory concluded, "we ought to take the country over and keep it." As an alternative, McKamey told Congressman McLemore that the United States should "buy a few of the northern states of Mexico" because it would be "cheap- er than going to war." The San Antonio Express urged the Mexican government to cooperate with Pershing's force to pursue those who participated in "organized murder, plundering and property destruction."

Woodrow Wilson and the Mexican Interventionist Movement of 1919

1919: William Jenkins, Robert Lansing, and the Mexican Interlude

Tempest in a Teapot? The Mexican-United States Intervention Crisis of 1919

Moving back to Europe once again and explaining my earlier statement of why Anti-Bolshevism being worse here, we must recall that even in victory, the Red Tide threatened to consume much of Europe. Italy had the Biennio Rosso, two years of unrest and violence rising to near Civil War levels; can one not envision at least a serious Bolshevik attempt to completely take over following a disastrous defeat after years of massive bloodshed? How about France, which had already seen massive unrest in 1917 and in 1920 had far left elements show a strong showing in the elections; they too could be radicalized via the defeat of France the same way German Bolsheviks were.

It may perhaps be surprising, but even Britain was not immune to this Red threat, herself very nearly succumbing to an attempted Revolution. To quote from The Russian Revolution and the British working class:

At the beginning of 1919 there was a huge wave of troop mutinies across Britain. Soldiers opposed attempts to send them to fight against the Bolshevik government, demanding to be demobilised. Most impressively there were a number of mutinies by British troops in Russia which helped to end the British attempts to crush the revolution.

The revolution gave direction to the disparate British revolutionary forces in their sometimes faltering attempts to intervene in events and to come together as a single revolutionary party. It led to the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1920 which included most of the best revolutionary activists.

This article explores the interplay between the revolutionary events in Russia and the deepening political crisis in Britain. Critically this was not simply about the motivating effect of Russia on British workers; equally the successful efforts of British workers to prevent intervention in Russia in 1919 and 1920 played a crucial role in holding back British imperial goals.

The revolution gave direction to the disparate British revolutionary forces in their sometimes faltering attempts to intervene in events and to come together as a single revolutionary party. It led to the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1920 which included most of the best revolutionary activists.

This article explores the interplay between the revolutionary events in Russia and the deepening political crisis in Britain. Critically this was not simply about the motivating effect of Russia on British workers; equally the successful efforts of British workers to prevent intervention in Russia in 1919 and 1920 played a crucial role in holding back British imperial goals.

As the article goes on to note, 1919 was the worst year in that critical time period for Britain, with over 2.59 million workers involved in 1,352 work stoppages and over 34,000 working days lost as a result. The article is also backed up by 1919: Britain on the Brink of Revolution:

The first mutiny broke out in Folkestone on 3 January 1919. Orders were posted in No.1 Rest Camp that 1,000 men were to parade at 0815 hours to embark for France, followed by a further 1,000 at 0825 hours. A soldier had written over the orders “No men to parade”. Not a single man turned out. Word then quickly spread through the town’s three camps and 3,000 men from the first camp had decide not to march to the ship but march on the town hall, where they held a meeting.

Men from other camps rushed to join them and some 10,000 soldiers assembled outside of Folkestone town hall. Speeches were made complaining about conditions and how they were being treated. When the town mayor showed up and reassured the men, he was met with the chorus of a popular song, “Tell me the Old, Old Story”!

The men were then addressed by the Lieutenant Commander who assured them there was to be no compulsory embarkation to France. The mail boat sailed to France with no soldiers on board. However, the next day new orders were issued proposing a certain quota. This provoked a further demonstration, this time at the harbour. This met the troop trains carrying those returning from leave, who immediately joined the strike. The armed guards at the harbour entrance were withdrawn as strikers threatened to collect their own weapons and return.

There were similar protests at Dover on the same morning, when about 2,000 troops turned back from Admiralty Pier where they were supposed to board a ship for France. They met the trains full of soldiers, who quickly joined them. They marched in full field kit and rifles, representing scores of different units, to the town hall to put their grievances. They then proceeded to form a Soldiers’ Union and elected a committee entirely of rank and file.

In several parts, especially in camps in and around London, mutineers commandeered lorries and drove to Whitehall to deliver their protests directly. On 9 January, 1,500 soldiers based at Park Royal in west London marched on Downing Street to confront Lloyd George and the Cabinet. Cunning Lloyd George was prepared to meet the men, but Lord Milner advised against as “similar processions would march on London from all over the country.” General Sir Henry Wilson declared that “the Prime Minister should not confer with soldiers who had disregarded their officers. The solders’ delegation bore a dangerous resemblance to a Soviet. If such a practice were to spread, the consequences would be disastrous.”

Instead, General Sir William Robertson was sent out to meet a delegation and agreed to their demands for better conditions and an end to the draft for Russia. The troops then returned to barracks.

British troops were also affected in Calais. Soldiers were proving equally unwilling to fight and to obey orders. Towards the end of January 1919, the men of the Army Ordnance and Mechanical Transport sections at the Val de Lievre camp organised a mass meeting which took the decision to mutiny. The mutiny broke out after agitation for demobilisation as the arrest of Private John Pantling, of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who had had a speech described by the authorities as a “seditious speech to an assembly of soldiers.”

Rebel soldiers broke into the prison and released Pantling. Military police were brought in to restore order, but the growing anger forced the Commanding Officer to relent and offer concessions. Word spread and Soldiers’ Councils were organised in other camps. When the authorities attempted again to arrest Pantling, the Soldiers’ Councils called a strike, which was completely solid. The guards were replaced by pickets

At another camp in nearby Vendreux, over 2,000 men struck in solidarity. Then they marched to the Calais camp. Following a mass meeting the combined forces marched behind brass bands towards army headquarters. The headquarters were rapidly surrounded by 4,000 mutineers, who demanded the release of Private Pantling, which was acceded to.

The next day, some 20,000 men had joined the mutiny. French troops fraternised as a total embargo was placed upon the movement of British military traffic by train. This stoppage led to 5,000 infantrymen due to return home, joining the demand for immediate demobilisation.

General Julian Byng attempted to call for reinforcements, but they proved equally unreliable in face of the growing mutiny.

The strike, coordinated by the strike committee, was solid. The committee took the title of “The Calais Soldiers' and Sailors' Association.” It was organised on democratic lines, where each group elected a delegate to the Camp Committee, which in turn sent delegates to the Central Area Committee. They ran everything and issued daily orders from the occupied Headquarters.

Soldiers at Dunkirk were also ready to come out. Even the women of the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary came out in solidarity with the Calais strike. The Calais Area Soldiers' and Sailors' Association continued to meet and applied for representation on the newly formed Soldiers', Sailors' and Airmen's Union. The union continued to grow for five months, claiming 49 branches, including Calais and Boulogne, by the beginning of April. The Calais mutiny, which had clearly have developed a revolutionary character.

On January 30 1919, General Byng finally surrounded Calais with troops equipped with armoured cars and machine guns. However, fraternisation continued between the forces. General Haig wanted the leaders of the Calais mutiny shot. However, the government feared provoking an explosion. There was no soldier punished for the incident despite the fact that mutiny was punishable by death.

The only reprisals were in the navy, where one sailor was sentenced to two years’ hard labour, three to one year and three to ninety days’ detention for refusing to go to sea, taking over the patrol vessel HMS Kilbride at Milford Haven, hauling down the white ensign and hoisting the red flag instead.

The nerves of the General Staff were clearly affected by the revolts. “We are sitting on top of a mine which may go up at any moment”, stated General Wilson to Churchill. Churchill himself feared that the unrest would spread and that “widespread disobedience would encourage Bolshevism in Britain.”

So concerned, Lloyd George rushed back from Paris on 8 February. As he arrived, some 3,000 soldiers from different camps were marching from Victoria Station to Whitehall in protest at food and sleeping arrangements. They were stopped at Horse Guard Parade by a battalion of Grenadier Guards with fixed bayonets, who shepherded them to as far as near Wellington barracks.

Men from other camps rushed to join them and some 10,000 soldiers assembled outside of Folkestone town hall. Speeches were made complaining about conditions and how they were being treated. When the town mayor showed up and reassured the men, he was met with the chorus of a popular song, “Tell me the Old, Old Story”!

The men were then addressed by the Lieutenant Commander who assured them there was to be no compulsory embarkation to France. The mail boat sailed to France with no soldiers on board. However, the next day new orders were issued proposing a certain quota. This provoked a further demonstration, this time at the harbour. This met the troop trains carrying those returning from leave, who immediately joined the strike. The armed guards at the harbour entrance were withdrawn as strikers threatened to collect their own weapons and return.

There were similar protests at Dover on the same morning, when about 2,000 troops turned back from Admiralty Pier where they were supposed to board a ship for France. They met the trains full of soldiers, who quickly joined them. They marched in full field kit and rifles, representing scores of different units, to the town hall to put their grievances. They then proceeded to form a Soldiers’ Union and elected a committee entirely of rank and file.

In several parts, especially in camps in and around London, mutineers commandeered lorries and drove to Whitehall to deliver their protests directly. On 9 January, 1,500 soldiers based at Park Royal in west London marched on Downing Street to confront Lloyd George and the Cabinet. Cunning Lloyd George was prepared to meet the men, but Lord Milner advised against as “similar processions would march on London from all over the country.” General Sir Henry Wilson declared that “the Prime Minister should not confer with soldiers who had disregarded their officers. The solders’ delegation bore a dangerous resemblance to a Soviet. If such a practice were to spread, the consequences would be disastrous.”

Instead, General Sir William Robertson was sent out to meet a delegation and agreed to their demands for better conditions and an end to the draft for Russia. The troops then returned to barracks.

British troops were also affected in Calais. Soldiers were proving equally unwilling to fight and to obey orders. Towards the end of January 1919, the men of the Army Ordnance and Mechanical Transport sections at the Val de Lievre camp organised a mass meeting which took the decision to mutiny. The mutiny broke out after agitation for demobilisation as the arrest of Private John Pantling, of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who had had a speech described by the authorities as a “seditious speech to an assembly of soldiers.”

Rebel soldiers broke into the prison and released Pantling. Military police were brought in to restore order, but the growing anger forced the Commanding Officer to relent and offer concessions. Word spread and Soldiers’ Councils were organised in other camps. When the authorities attempted again to arrest Pantling, the Soldiers’ Councils called a strike, which was completely solid. The guards were replaced by pickets

At another camp in nearby Vendreux, over 2,000 men struck in solidarity. Then they marched to the Calais camp. Following a mass meeting the combined forces marched behind brass bands towards army headquarters. The headquarters were rapidly surrounded by 4,000 mutineers, who demanded the release of Private Pantling, which was acceded to.

The next day, some 20,000 men had joined the mutiny. French troops fraternised as a total embargo was placed upon the movement of British military traffic by train. This stoppage led to 5,000 infantrymen due to return home, joining the demand for immediate demobilisation.

General Julian Byng attempted to call for reinforcements, but they proved equally unreliable in face of the growing mutiny.

The strike, coordinated by the strike committee, was solid. The committee took the title of “The Calais Soldiers' and Sailors' Association.” It was organised on democratic lines, where each group elected a delegate to the Camp Committee, which in turn sent delegates to the Central Area Committee. They ran everything and issued daily orders from the occupied Headquarters.

Soldiers at Dunkirk were also ready to come out. Even the women of the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary came out in solidarity with the Calais strike. The Calais Area Soldiers' and Sailors' Association continued to meet and applied for representation on the newly formed Soldiers', Sailors' and Airmen's Union. The union continued to grow for five months, claiming 49 branches, including Calais and Boulogne, by the beginning of April. The Calais mutiny, which had clearly have developed a revolutionary character.

On January 30 1919, General Byng finally surrounded Calais with troops equipped with armoured cars and machine guns. However, fraternisation continued between the forces. General Haig wanted the leaders of the Calais mutiny shot. However, the government feared provoking an explosion. There was no soldier punished for the incident despite the fact that mutiny was punishable by death.

The only reprisals were in the navy, where one sailor was sentenced to two years’ hard labour, three to one year and three to ninety days’ detention for refusing to go to sea, taking over the patrol vessel HMS Kilbride at Milford Haven, hauling down the white ensign and hoisting the red flag instead.

The nerves of the General Staff were clearly affected by the revolts. “We are sitting on top of a mine which may go up at any moment”, stated General Wilson to Churchill. Churchill himself feared that the unrest would spread and that “widespread disobedience would encourage Bolshevism in Britain.”

So concerned, Lloyd George rushed back from Paris on 8 February. As he arrived, some 3,000 soldiers from different camps were marching from Victoria Station to Whitehall in protest at food and sleeping arrangements. They were stopped at Horse Guard Parade by a battalion of Grenadier Guards with fixed bayonets, who shepherded them to as far as near Wellington barracks.

On the whole, there is a serious risk that many of the now defeated Entente powers could slip into Bolshevik control or, at the very least, civil war initiated by the same. German bayonets would probably allow Anti-Communist forces to prevail in France and Italy, but Britain, given its position as an island, holds a very real risk indeed. Thus, it is entirely possible that as Germany and America reach for their Imperial goals, the British Empire could collapse as the Home Island falls to Revolution. That this would open up opportunities for other players, such as the United States, Germany, the Ottomans, etc cannot be ignored. Although his comments are on a different scenario (America staying neutral in 1917), H.L. Mencken provides some insights in this regard that I feel could prove useful in our speculations:

Baltimore Evening Sun, Nov. 11, 1931, "A Bad Guess" by H. L. Mencken:

The United States made a similar mistake in 1917. Our real interests at the time were on the side of the Germans, whose general attitude of mind is far more American than that of any other people. If we had gone in on their side, England would be moribund today, and the dreadful job of pulling her down, which will now take us forty or filthy years, would be over. We'd have a free hand in the Pacific, and Germany would be running the whole [European] Continent like a house of correction. In return for our connivance there she'd be glad to give us whatever we wanted elsewhere. There would be no Bolshevism [communism] in Russia and no Fascism in Italy. Our debtors would all be able to pay us. The Japs would be docile, and we'd be reorganizing Canada and probably also Australia. But we succumbed to a college professor [Wilson] who read Matthew Arnold, just as the English succumbed to a gay old dog who couldn't bear to think of Prussian MP's shutting down the Paris night-clubs.

On a final note, with the Red Scare being so much worse in 1919 and likely large numbers of IOTL Fascist Italians running about given the disorder in Italy, I wouldn't be surprised if the United States ended up becoming Fascist in this ATL. Henry Ford came close to winning a Senate seat in 1918 for Michigan and could serve as the Salazar or Hindenburg for such a regime later on, with men like Father Coughlin as the Goebbels of the regime, Huey Long as the Hitler, and Ezra Pound as the Bormann, etc.