lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 23, 2020 8:07:02 GMT

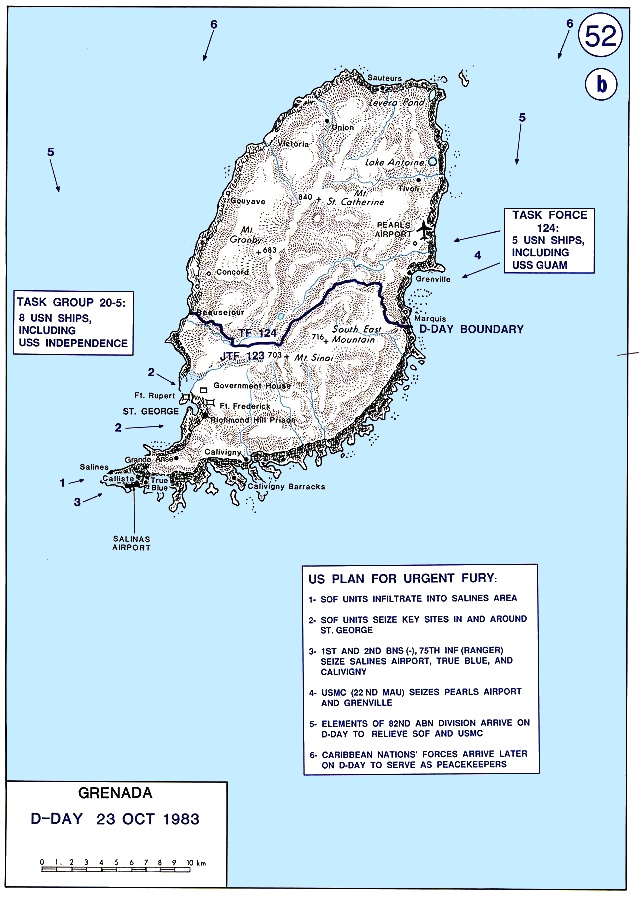

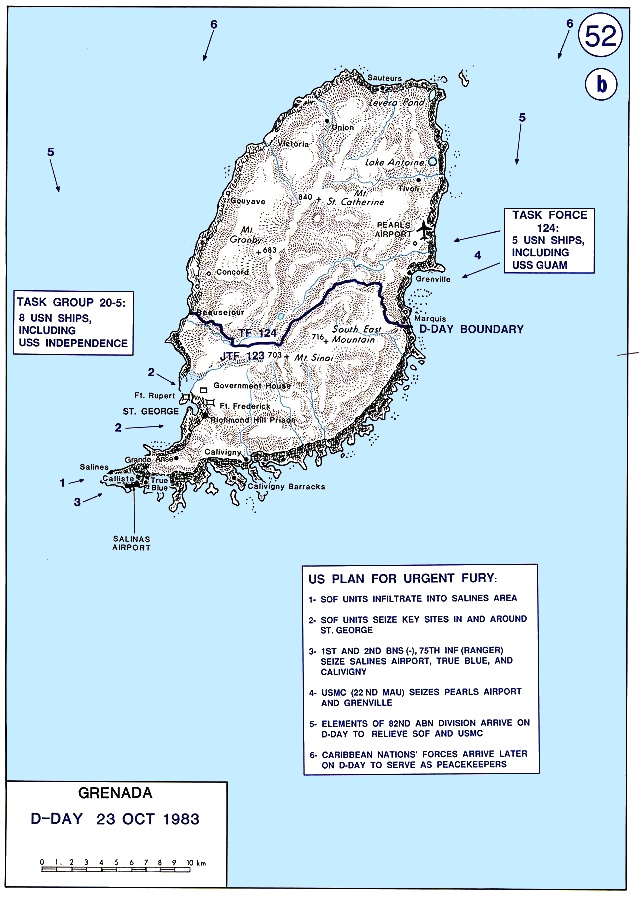

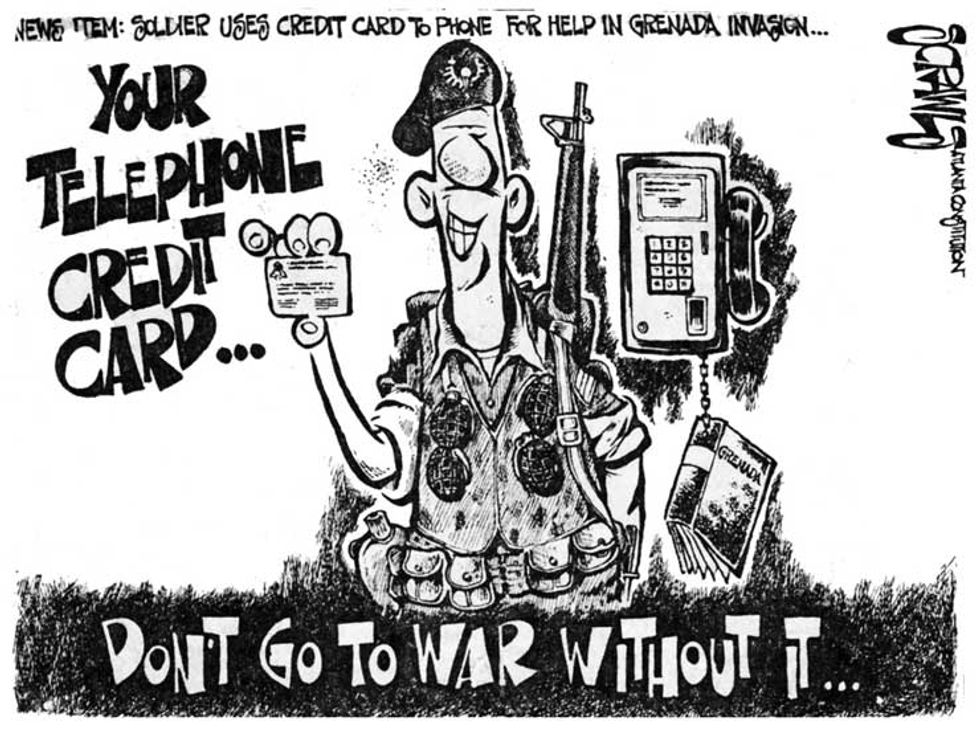

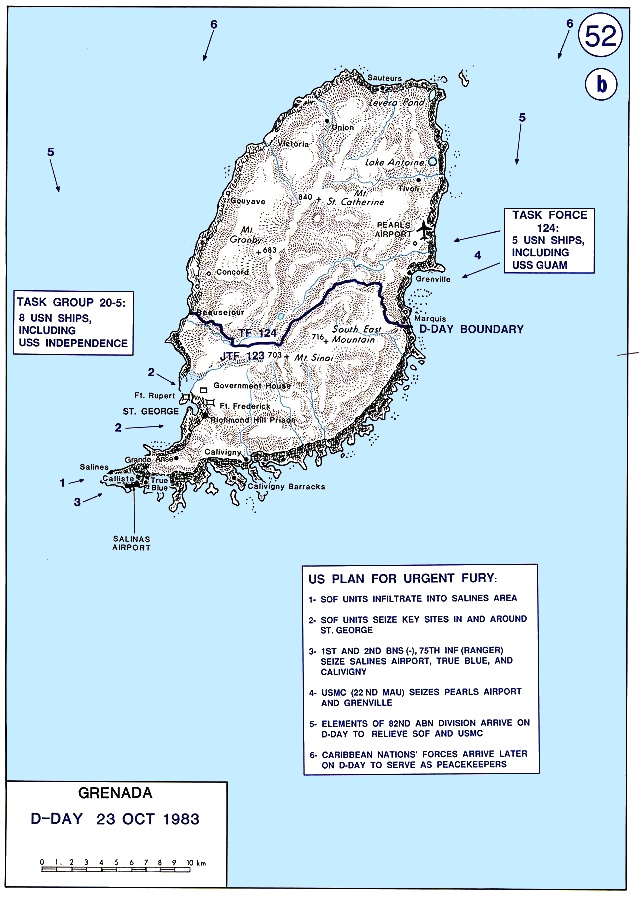

United States invasion of Grenada 1983 - Operation Urgent Fury in realtime Grenada lies between Puerto Rico and Venezuela and was an unlikely location for a showdown between the Western democracies and communism. Yet, it was on the small island that the Brezhnev Doctrine—in essence that the Soviet Union would ensure that any government that became communist would remain so forever—met its first reversal. At the end of a three-day battle Grenada would return to the family of democratic nations. Moreover, the fight set in motion forces that fundamentally changed American military operations. Grenada had a long and bloody history well before the American invasion. The centuries following the island’s 1498 “discovery” by Christopher Columbus were marked by rebellion and a British-French power struggle. Britain finally granted the island independence in 1974, ending more than 300 years of colonial rule. For the next five years Prime Minister Eric Gairy, supported by vicious political “mongoose gangs” (so named because they initially came together in a government program to eradicate the island’s mongoose population), ruled the country. That rule ended in March 1979, when Maurice Bishop, head of the Marxist New JEWEL (Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education, and Liberation) Movement, or NJM, staged an armed coup while Gairy was in New York trying to persuade the United Nations to conduct research on extraterrestrial life and UFOs. Many Grenadians welcomed the coup, although the new regime—the People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG)— soon proved as corrupt and vicious as Gairy’s. In a bid for financial support and to enhance his own security, Bishop closely allied himself with Cuba. In turn, the Cubans sent a military mission to help train Grenada’s new People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA) and People’s Revolutionary Militia (PRM), using weapons provided by the Soviet Union. Cuba also sent men and materiel for the construction of an international airport at Point Salines, the island’s southwestern tip. A 650-man Cuban army workforce toiled to complete the runway by March 1984, the revolution’s fifth anniversary. By 1983, however, the PRG was splintering. An opposition group led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard determined that Bishop’s ideological beliefs were insufficiently pure and began plotting a takeover. As the factions moved toward a showdown, Bishop had popular backing, while Coard held the loyalty of the military. Striking first, on Oct. 14th 1983, Coard had Bishop and other officials—including education minister Jacqueline Creft, Bishop’s mistress—placed under house arrest. To many Grenadians the charismatic Bishop was the island’s first truly authentic leader, representing freedom from both Great Britain and Gairy’s thugs. On the morning of October 19 thousands of Bishop’s supporters marched on his residence in Grenada’s capital of St. George’s, chanting, “We want Maurice!” Despite the presence of armored personnel carriers and soldiers, the crowd freed Bishop, Creft and the other ministers and spirited them to the army’s headquarters at Fort Rupert, a mile and a half away. This journey took Bishop and his supporters right past Coard’s residence, where he crouched, defenseless, waiting for Bishop’s retribution. It never came. For reasons unknown, Coard was allowed to remain unmolested and able to regroup —a mistake Bishop would soon regret. As Bishop and his advisers met at Fort Rupert, Coard and the PRA stormed the installation. Three armored personnel carriers plowed through the thousands of Grenadians gathered to hear Bishop speak, killing scores of them. Within minutes the insurgents had taken the fort and re-arrested Bishop, Creft and the other four ministers. Learning from past experience, Coard ordered the prisoners’ summary execution. He then sought Cuban support for his coup. But Fidel Castro had considered Bishop a personal friend and refused additional aid. Coard then turned to the Soviet Union, with whom he was more closely aligned than Bishop. However, despite having sent military materiel, Moscow attached little strategic importance to Grenada and deemed such direct intervention in America’s backyard too great a risk. Realizing he was a liability to the Marxist cause, Coard resigned his position. Panicking, the new regime imposed a 24-hour “shoot to kill” curfew on the island and broadcast pleas for unity under the revolutionary motto “Forward Ever, Backward Never.” The Revolutionary Military Council was playing for time. The most compelling reason for the United States’ keen interest in Grenada was geopolitical. There was growing unease in American policy circles about the wisdom of allowing the Cubans and Soviets to create a satellite so close to vital shipping lanes. These concerns intensified as it became clear the Soviets were supporting communist movements in nearby El Salvador and Nicaragua. Taken together, Cuba, Nicaragua and Grenada enveloped the Caribbean in a strategic triangle, through which half of any U.S. wartime reinforcements to NATO would have to pass. What put Washington policymakers on high alert, however, was the start of construction on a new airfield capable of handling the largest Soviet military transports. The Reagan administration doubted Grenada’s claims the field was meant solely to support tourism, as there was no concomitant building of the hotels and resorts one would expect to accompany such an initiative. Once completed, the airfield would give the Soviets a forward base in an area the United States considered vital to its security. The growing political chaos in Grenada thus offered Washington the opportunity to return one small nation to the democratic fold, while at the same time restricting the expansion of Soviet influence in the region. Moreover, Grenada offered the U.S. military a chance to bolster its reputation, which had suffered with the withdrawal from Vietnam, the humiliating failures during the 1975 Mayaguez incident and the failed 1980 Iranian hostage rescue. The latter debacle had particular resonance: By 1983 more than 650 American students were enrolled in Grenada’s St. George’s University School of Medicine. Although there was no initial threat, the specter of the Grenadian government holding hundreds of American students hostage haunted Reagan and his cabinet. It was this threat that provided the incentive for rapid action on what became a rescue mission—it was never officially referred to as an invasion. Planning for Operation Urgent Fury picked up speed on October 19, when Milan Bish, the State Department’s ambassador in Barbados, reported to Washington that the United States “should now be prepared to conduct an emergency evacuation of U.S. citizens in Grenada.” Within days the final directive was ready for presidential approval. It called for ensuring the safety of American citizens, restoring democratic government on Grenada and preventing Cuban intervention, and it authorized a full-scale, joint-forces invasion conducted with the participation of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States. Such a mission appeared to require, by law, the consent of Congress. But since a hostage rescue demands complete surprise, the Reagan administration had a handy excuse for skirting the War Powers Act and keeping Congress in the dark until the operation was under way. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff handed Operation Urgent Fury to Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf III’s Joint Task Force 120, which comprised the 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit, the Joint Special Operations Command and the 82nd Airborne Division. Since the invasion was precisely the kind of mission for which special operations forces trained, JSOC played a leading role from the start. Its Task Force 123 included Army Ranger battalions and Delta Force operators, Navy SEALs and Air Force Combat Control Teams. Major General Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. was pulled from command of the 24th Infantry Division and made Metcalf’s senior Army adviser. Metcalf’s newly formed JTF 120 had less than four days to finalize the Grenada plan and launch the operation. Doing so meant overcoming such obstacles as the lack of military maps or on-site intelligence and the fact that none of the units involved had previously planned or trained together. The final outline called for the invasion to commence at 2 a.m. on October 25. TF 123 would take the southern end of the island, with the Rangers parachuting onto and securing the Point Salines airfield, then moving on the Calivigny barracks and True Blue campus of the medical school. The SEALs and Delta troops would handle the area around St. George’s, while the Marines were to land in the north and secure Pearls airfield. All of these objectives—including the safe release of the medical students and Commonwealth Governor-General Sir Paul Scoon—were scheduled for completion within four hours of the initial assault, at which point the 82nd would land at Salines and restore law and order. If all went as planned, the Americans would then hand over peacekeeping duties to a Caribbean force and head for home. Prelude to Operation Urgent Fury , Sunday, October 23rd 198312 Navy SEALs and four Air Force Combat Control Team members are parachuted into dark Caribbean waves whipped by 25-knot winds. The men are supposed to clamber aboard two air-dropped Zodiac inflatable boats and slip ashore at Salines airfield to position aircraft beacons for the next day’s Ranger drop. The mission is plagued with mishaps however. On hitting the water, four SEALs drown. The remaining men pile into one boat, but are forced to kill its engine when a Grenadian patrol craft approached. The engine fails to restart and the SEALs have to wait for rescue by a surface vessel. The operation is only two hours old, and already the first force deployed has failed in its mission and suffered 25 % casualties. Map: Map of invasion plan

|

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,843

Likes: 13,230

|

Post by stevep on Oct 23, 2020 11:05:21 GMT

lordroel , Interesting. I remember there was concern about Cuba supporting the 'regime' and IIRC talk about a lot of Cubans on the island so a bit of a surprise that neither they nor the Soviets were actively involved. Know it caused a fair bit of a storm at the time but didn't realise the situation on the island was such a shambles.

Be interesting to see how the rest of the invasion goes. Hadn't hard of the early disaster of the special forces operation but know of course that the US wins fairly quickly.

Steve

|

|

gillan1220

Fleet admiral

I've been depressed recently. Slow replies coming in the next few days.

Posts: 12,609

Likes: 11,326

|

Post by gillan1220 on Oct 23, 2020 16:27:48 GMT

I know for one the Soviets were not willing to go to war over Grenada. What was closer was in Lebanon which the U.S. Marine barracks was bombed and the Iowa-class battleships saw action again.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 24, 2020 7:10:31 GMT

Prelude to Operation Urgent Fury , Monday, October 24th 1983

Political events

British PM Margaret Thatcher attempts to dissuade Reagan administration from military action in Grenada. Combat operations (Air, Land and Sea)General Trobaugh overall ground forces commander briefs his officers on the final invasion plans and makes it clear, this is a “real-world” mission, not a drill. Photo: U.S. Army soldiers of the 82nd Airborne Division in a heavily loaded M151 light vehicle prepare to depart for Grenada from Pope Air Force Base, North Carolina (USA)

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 25, 2020 7:47:42 GMT

DAY 1 of Operation Urgent Fury, Tuesday, October 25th 1983YouTube (U.S. Invades Grenada, October 25th 1983)Combat operations (Air, Land and Sea)United States Army Rangers and other special operations forces of the Joint Special Operations Command, including the helicopters of the 160th Aviation Battalion—designated Task Force 160 and commanded by Lt. Col. Terence M. Henry—were the spearhead force for the operation. The Rangers of the 1st Battalion, 75th Infantry, had departed Hunter Army Airfield at 2230 the night before in C–130s. The uncertainty of the situation on Grenada, like the confusion of the 82d Airborne Division, led the Rangers, except for the lead assault company, to rig for airlanding, not for airdrop. During the flight, however, Colonel Taylor received additional intelligence that the Cubans had placed obstacles on the runway, making airlanding unlikely. He believed that if he parachuted only one company down to clear the obstacles they would be dangerously exposed, with no chance of reinforcement. He therefore decided, just in case, to rig the entire battalion for airdrop and gave the order during the flight. It was well he did. The first two planes with the lead assault company had to abort their drops because of failures in their inertial navigation system and radar. Not originally scheduled as the lead assault element, the Rangers were then air-dropped from the third plane. They jumped in the face of moderate antiaircraft fire beginning at 0530. Assisted by circling Air Force AC–130 Spectre gunships, the Rangers hit the ground, returned fire, and set up their command post. Photo: Rangers parachute onto Point Salines early in the morning of October 25th 1983 Almost simultaneously with the Ranger attack, a company of the 2d Battalion, 8th Marines, landed by helicopter south of Pearls Airport on the east coast of Grenada. A Grenadian attempt to engage the helicopters with antiaircraft fire ended when Marine AH–1 Cobra gunships silenced the threat. The marines moved out to the north to secure the airfield, encountering only light resistance. Map: Initial troop invasion areas

The special operations forces’ effort to rescue Governor General Sir Paul Scoon in St. George’s did not go as smoothly. The helicopters of the supporting Task Force 160 had arrived late at the intermediate staging base in Barbados and did not depart until 0530, well after dawn and a half hour after the planned attack time. As a result, the assault force, consisting of lightly armed Navy SEALs (sea-air-land commandos) and their Army special operations counterparts, was fully exposed to enemy fire. After rappelling from their helicopters to the ground near the governor general’s residence and securing Sir Paul, the special operators found themselves under attack by Grenadian forces including armored cars. Lacking antitank weapons, they called in air strikes from circling AC–130s, Marine helicopters, and Navy A–7 Corsair fighter-bombers, battling the enemy all day and into the night. Photo: A U.S. Army AH-1S Cobra attack helicopter opens fire on an enemy position

Other special operations attacks that day were even less successful. Attempts to silence Radio Free Grenada by capturing the main radio transmitter were unsuccessful. It was later discovered that the Grenadians had alternate transmitters for the station. Counterattacks drove the Americans into the jungle in a hasty retreat. Daylight attacks against objectives at the Richmond Hill prison and Fort Rupert also failed after withering antiaircraft fire severely damaged the helicopters involved in the assault. Two of the helicopters crashed, killing one of the pilots, Capt. Keith J. Lucas. Two Marine AH–1 Cobra gunships were also shot down by antiaircraft fire from nearby Fort Frederick. Three of the four crew members were killed. Meanwhile, the Ranger attack at Point Salines slowly gathered steam. Using two-man teams to clear the vehicles that the Cubans had parked on the runway (in some cases conveniently leaving the keys in the ignition), the Rangers were able to ready the airfield to receive planes. But the Rangers also had to suppress the antiaircraft fire, and they quickly called in AC–130s to finish the job. Small arms fire from the Cubans and Grenadians continued, however, although it affected troops on the ground more than aircraft. Still, with two companies on the ground, the Rangers were able to shift to the high ground to their east and capture about two hundred Cubans. As they continued on toward the Cubans’ construction camp, they took an additional twenty-two prisoners. The airfield was declared secured at 0735. The first C–130 touched down moments later. Photo: Bombardment of Point Calivigny

Even as the airfield was secured, the Rangers began to push toward nearby high ground to silence enemy snipers. They enlisted airpower and even commandeered a Cuban bulldozer to assist. S. Sgt. Manous F. Boles Jr., a member of the runway-clearing team, put the blade of the bulldozer up for protection against small arms fire and drove it up the hill with a squad following behind to take the heights. Ranger mobility improved when aircraft delivered long-awaited gun jeeps. One jeep immediately loaded up with soldiers and drove off to establish an outpost to protect the nearby True Blue medical school campus. The Rangers, however, lost their way and were ambushed. Four Rangers were killed and one badly wounded. Photo: U.S. Army soldiers of 1st Platoon A Co. 1st Bn ABN/508th Inf,82d Airborne Division on patrol. Two of the soldiers (facing left foreground) on the road have M47 Dragon antitank weapons.

By midday, all of the close high ground surrounding the airfield was in friendly hands. Using a captured antiaircraft gun on the heights near a Cuban Army compound north of the village of Calliste, the Rangers forced the surrender of one hundred fifty more Cubans. Only eighty Cubans remained unaccounted for, and enemy fire slackened considerably. Meanwhile, the Rangers set up a detainee collection and interrogation point near the airfield. The Rangers retained custody of the detainees for only a few hours before they turned them over to the lead elements of a 300-man Caribbean Peacekeeping Force arriving in an Air Force C–130. The U.S. military and civilian leadership, recognizing the public relations value of an international armed contingent and its lack of training for combat, had arranged for these troops to assume peacekeeping and detainee control duties. Photo: Members of the Eastern Caribbean Defense Force

Being freed from detainee guard duty and not wishing to commit his reduced force to the second mission, the seizure of Calivigny Barracks, General Sholtes awaited the arrival of the follow-on 82d Airborne Division elements. They began arriving by airplane and not by parachute assault at 1400. With the airfield secure, General Trobaugh had decided that the risks of losing men in the ocean (the paratroopers had not been issued flotation devices) outweighed whatever advantages of mass that might be achieved by a parachute assault. Though the airfield could only handle one plane at a time, the troops would be much less scattered and less likely to suffer the normal accidents and breakages attendant to any parachute drop. Even as the command group for the 82d Airborne Division gathered on the island, linked up with the Rangers, and began to assess the fluid situation, a larger problem erupted. When the Rangers had moved to rescue the American medical school students at the True Blue campus, they found only about one hundred forty students. The students told the Rangers that there was a larger campus with even more students—around two hundred—at Grand Anse a few miles to the north. This was the first the Americans had heard of this second campus. No plans existed to capture it. The frail security of the perimeter protecting the airfield was underscored by an incident about 1530. Company A of the 2d Battalion, 325th Infantry, was reinforcing some Ranger positions near the True Blue campus when three BTR60 armored personnel carriers attacked, pushing down the road from the university campus. The soldiers of the Grenadian Army’s Motorized Company drove directly into the Ranger’s positions, firing their machine guns wildly in all directions. In response, the Rangers and the airborne troopers showered the vehicles with light antitank weapon (LAW) fire and 90-mm. recoilless rifle fire, which caused two vehicles to crash and their occupants to flee, leaving two dead behind. The third vehicle was fired on by a circling AC–130 and destroyed. Photo: A U.S. Navy Ling Temco Vought A-7E-4-CV Corsair II from attack squadron VA-87 Golden Warriors in flight over Port Salines airfield, Grenada. VA-87 was assigned to Carrier Air Wing 6 (CVW-6) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Independence (CV-62) Although this was the last major attack against the perimeter, the assault so surprised General Trobaugh that he requested reinforcements. Calling Fort Bragg on his satellite radio, he told his division rear staff, “Send me battalions until I tell you to stop.” This began the flow of additional infantry but severely disrupted the logistical stream as the combat forces received priority over support troops and supplies. He also asked for, and received, operational control over the Ranger battalions even though the original plan had them departing once the 82d took over the operation. While action continued around the airfield at Point Salines, air and naval forces raided enemy command posts in the Fort Frederick and Fort Rupert areas and pursued rescue of the cutoff SEALs at the governor general’s residence. A–7 Corsairs from the Independence attacked the two forts, accidentally hitting a hospital close to Fort Frederick and killing eighteen mental patients. They also struck the gun positions placed near the hospital by the Grenadian military. Around 1900, a landing force of about two hundred fifty marines with tanks and amphibious vehicles stormed ashore at Grand Mal Bay north of St. George’s and pushed south and east toward the governor general’s residence. Moving deliberately, the marines finally linked up with the beleaguered SEALs just after sunrise on the twenty-sixth. They flew Sir Paul, his wife, nine civilians, and the SEALs out to the USS Guam by helicopter at 1000. The marines then moved on to Fort Frederick to the east and quickly captured the fort. Photo: Three U.S. Army Sikorsky UH-60A Black Hawk helicopters prepare to touch down next to the Point Salines airport runway during "Operation Urgent Fury"

The 82d Airborne Division’s buildup of forces on the airfield continued throughout the afternoon and evening of 25–26 October. The last of the 2d Battalion, 325th Infantry, reached the airstrip before dusk, and the follow-on 3d Battalion of the 325th was in place early on the twenty-sixth. Supplies began to flow more easily as the pace of C–130 landings picked up, but quantities of food, water, and ammunition remained limited. Photo: A U.S. Marine Corps Bell UH-1N Huey helicopter from Marine medium helicopter transport squadron HMM-261 Raging Bulls during "Operation Urgent Fury". The helicopter is equipped with door-mounted M60D machine guns. In the background is a Sikorsky CH-53D Stallion helicopter.

|

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,843

Likes: 13,230

|

Post by stevep on Oct 25, 2020 11:13:01 GMT

Ah so there were Cubans there. I thought I remembered reports of them at the time. The earlier reference possibly meant that the Cubans decided not to reinforce the 'construction' personal who had been sent to the island.

Rather messy but then a lot can go wrong in a conflict, even a relatively small one like this. Possibly a very useful learning lesson for the US military before the liberation of Kuwait a few years later.

Steve

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 25, 2020 11:22:41 GMT

Ah so there were Cubans there. I thought I remembered reports of them at the time. The earlier reference possibly meant that the Cubans decided not to reinforce the 'construction' personal who had been sent to the island. Rather messy but then a lot can go wrong in a conflict, even a relatively small one like this. Possibly a very useful learning lesson for the US military before the liberation of Kuwait a few years later. Steve

This is dated on October 26th 1983 but i decided not post it in the next update, its a YouTube clip of Cuban Pres Fidel Castro saying he will not send reinforcements to back up the 600 Cubans on Grenada, as the US invasion force on the island is `too strong'. The Cuban commander on Grenada, Col Pedro Tortolo, has orders to receive and listen to a representative of the US. |

|

gillan1220

Fleet admiral

I've been depressed recently. Slow replies coming in the next few days.

Posts: 12,609

Likes: 11,326

|

Post by gillan1220 on Oct 25, 2020 12:50:28 GMT

Ah so there were Cubans there. I thought I remembered reports of them at the time. The earlier reference possibly meant that the Cubans decided not to reinforce the 'construction' personal who had been sent to the island.

Rather messy but then a lot can go wrong in a conflict, even a relatively small one like this. Possibly a very useful learning lesson for the US military before the liberation of Kuwait a few years later.

Steve

The North Koreans were there as well according to Global Security. |

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 26, 2020 3:47:14 GMT

DAY 2 of Operation Urgent Fury, Wednesday, October 26th 1983

Political events

British PM Thatcher angered over US invasion of Grenada. Pentagon expresses “sense of outrage” about Thatcher’s refusal to participate in invasion after the US’s assistance in the recapturing of the Falklands from the Argentinians the year prior. Combat operations (Air, Land and Sea)General Trobaugh’s priority on the morning of the twenty-sixth was to rescue the medical students at the newly “discovered” Grand Anse campus of the St. George’s University School of Medicine. However, the few helicopters available to him from the special operations aviation task force were too badly shot up for use, and his own helicopters had not yet arrived on the island. He decided to use his forces to consolidate his hold on the airfield—still subject to harassing sniper fire—and then move out in strength the next day to find the students. Photo: A U.S. Army Bell AH-1S Cobra helicopter flies over Sikorsky UH-60A Black Hawk helicopters at Port Salines airfield, Grenada on October 26th 1983.

The 2nd Brigade attack kicked off early on the twenty-sixth only to have a reconnaissance patrol near a hill at Calliste led by Capt. Michael F. Ritz of Company B, 2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry, ambushed by Cubans. Ritz was killed instantly, and his sergeant severely wounded. One of the company’s platoons then moved cautiously up the hill conducting reconnaissance by fire to flush out the Cubans. Locating some Russian hand grenades, the soldiers bombarded the Cuban positions and fire diminished but not before another soldier was killed and five more wounded. The fight had been an intense and costly one, with two American dead and six wounded in the space of a few minutes. After the firefight near Calliste, the main attack started at 0630. A combination of artillery fire and Navy fighter-bomber sorties against the center of enemy resistance, a Cuban compound, soon silenced the enemy guns and white flags began appearing. Though some of the Cubans escaped into the surrounding jungle, the main body of the Cuban “construction workers” surrendered, and the compound was secure by 0835. Photo: M102 howitzers of 1st Bn 320th FA, 82D Abn Div firing during battle The 2nd Brigade continued to move slowly north and east, expanding the perimeter around the airfield with only minor enemy contact. Despite a few heat casualties, the force advanced toward Frequente. Near Frequente, one of the companies, Company C, discovered a series of warehouses surrounded by barbed wire and chain-link fence. Inside the warehouses were enough Soviet- and Cuban-supplied small arms and military equipment to outfit six infantry battalions, far in excess of Grenadian military needs. While securing the warehouses, men from Company C watched as five gun jeeps of the battalion’s reconnaissance platoon were ambushed by Cubans. The Cubans let the first two jeeps go past and opened fire on the last three. The lead jeeps wheeled back toward the ambush zone with machine guns blazing. Company C opened fire as well and began placing mortar rounds on the Cuban positions. The Cubans broke contact and fled, leaving behind four dead. There were no U.S. casualties. The troops continued the advance east until sunset, when they halted and established a defensive perimeter. While the paratroopers pushed east and north, General Trobaugh ordered the Rangers of the 2nd Battalion, 75th Infantry, to launch a helicopter assault to rescue the American medical students at Grand Anse. He had wanted to delay the raid until the twenty-seventh, but at 1100 on the twenty-sixth he received a directive from the Joint Chiefs to rescue the students immediately. He assigned the mission to Colonel Hagler’s Rangers and borrowed some Marine helicopters from the Guam to transport them to Grand Anse. Hagler met with Col. James P. Faulkner, commander of the 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit, to work out the details. The rescue operation began late in the afternoon. Using Navy and Air Force planes for preparatory fires and fire support, Hagler’s Rangers flew in on six CH–46 Marine Sea Knight helicopters and seized the campus. Two companies secured a perimeter while the other company found the 233 students and led them to the waiting Sea Knights. The Grenadian defenders mounted only a token resistance before fleeing, and one Ranger was lightly wounded. One CH–46 crashed into the nearby surf when its blades hit a palm tree, but the evacuees were loaded onto other helicopters without further incident. With one less helicopter for the evacuation, eleven Rangers were forced to stay behind, but they borrowed a rubber raft from the downed helicopter and after dark paddled out to sea where they were picked up by an American destroyer, the USS Caron. But perhaps the most unsettling occurrence was when intelligence gained from the students indicated that there was yet a third area where large numbers of Americans resided, a peninsula on Prickly Bay (near Lance aux Épines) just east of Point Salines. Once again a lack of intelligence forced planners to readjust and prepare for another rescue mission. Photo: A Marine Corps Sea Knight helicopter sits on the beach after being disabled during the Grand Anse rescue on October 26th 1983 By the end of the day on the twenty-sixth, most objectives had been accomplished and the 82nd was well established in a perimeter along the Calivigny Peninsula. The plans for the following day included expanding the perimeter toward St. George’s in the north and receiving follow-on forces from the 3rd Brigade and pushing them to clear the southern portion of the island.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 27, 2020 3:47:55 GMT

DAY 3 of Operation Urgent Fury, Thursday, October 27th 1983YouTube (AP special report Granada, October 27th 1983)The third day of military operations saw the slow consolidation of U.S. forces on the island. The marines fanned out from their positions in the St. George’s area and occupied Fort Lucas, Richmond Hill prison, and other sites without opposition. The paratroopers of the 2nd and 3rd Brigades of the 82nd Airborne Division, being surprised by the strength of Cuban resistance on the island and wondering if a guerrilla war was in their future, moved east from the airfield and cleared any lingering opposition. Still lacking effective helicopter and artillery support, the paratroopers depended for most of their fires on naval close air and gunfire, but insufficient direct communications with the ships caused requests for fire to be relayed back to Fort Bragg and then by satellite to the ships. Photo: U.S. troops armed with LAW rockets (Light Anti-Tank Weapons) take up position on a hill to provide over-watch of an assault against armed Cuban military forces on the Island. Once the 2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry, arrived in the Grand Anse area, it found only discarded Grenadian Army uniforms and equipment, indicating a collapse of resistance. The paratroopers also discovered about twenty American medical students that the Rangers missed the day before. Except for a few sniper attacks, the movement north toward St. George’s occurred without incident. The 3rd Battalion, to the right of the 2nd, advanced north toward St. George’s along the True Blue–Grand Anse road. Just short of the village of Ruth Howard, the soldiers were surprised by a crowd of celebrating civilians who began welcoming the startled paratroopers as liberators. The celebration ended abruptly with snipers firing on the crowd, but rapid and accurate return fire ended the attack. The battalion continued north and then east toward the highlands through rough and trackless terrain. One friendly fire incident in the late afternoon of the twenty-seventh marred the otherwise uneventful movement of the 3rd Battalion from the airfield. As one of the companies moved up to Ruth Howard, it was met by elements of an ANGLICO team (Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Company) at the crossroads. Suddenly, they came under fire. The marines of the ANGLICO element identified what they thought was the enemy position and called in an A–7 Corsair. Several dry runs over the target seemed to indicate that the pilot knew where to fire, but on the fourth, live-fire, strafing run, the plane deviated slightly and shot directly into the nearby command post of the 2nd Brigade. Seventeen members of the brigade staff were wounded, three of them seriously. One subsequently died of his wounds Photo: Members of the Eastern Caribbean Defense Force participating in Operation URGENT FURY. They are armed with a Belgian made 7.62 mm FN FAL rifles.

The other military operation that day was an unexpected launch of an air assault by Hagler’s 2nd Battalion. General Trobaugh had planned to take the Calivigny military barracks the next day, but an order from someone on the Joint Chiefs of Staff (exactly who sent the command and under whose authority it was sent was never determined) demanded that the joint task force capture the barracks “before dark” on the twenty seventh. No reason was given for this long-distance micromanagement of a tactical battle, but after several attempts to clarify the order failed, General Trobaugh directed the Rangers to prepare for the mission, even though they had conducted two air assaults already and were relaxing at the airfield, expecting to go home. Trobaugh turned to the commander of his 3rd Brigade, Col. James T. Scott, to coordinate the operation, which involved both the 2nd Battalion and Company C of the 1st Battalion. Colonel Scott was the logical choice for this mission involving multiple commands. He had only given up command of the 1st Battalion (Rangers) the previous May and was well known to both battalion commanders and their staffs. Intelligence on Calivigny was poor, but it was suspected that the enemy had antiaircraft gun emplacements protecting the barracks, making a daylight air assault risky. It was also possible that a battalion of the Grenadian Army and perhaps as many as three hundred to four hundred Cubans (with some Soviet advisers) were prepared to defend the barracks. Trobaugh and Scott decided to err on the side of caution given the recent proof of how costly daylight helicopter raids could be. With little more than fifteen minutes to plan the assault, the Rangers boarded their UH–60 Black Hawk helicopters. A few artillery rounds were fired on the landing zone, but most of them did not fall on target. Air support was more effective and, as the helicopters took off from Point Salines, the men could see plumes of smoke from the burning buildings of the barracks in the distance. No antiaircraft fire greeted the helicopters at the landing zones, and only a few Grenadian soldiers were in evidence to make a token resistance. Nevertheless, a few rounds from small arms from the ground (perhaps exploding rounds resulting from the air strikes on enemy ammunition dumps) hit the lead helicopters, severing hydraulic lines and causing one helicopter to crash into another. Photo: Two aerial photographs showing the Calivigny military barracks at Egmont, Grenada, before and after attacks of U.S. Navy aircraft from the aircraft carrier USS Independence (CV-62) The two helicopters went down in a tangled mess. Nearby, a third one unexpectedly landed in a ditch, striking the tail boom and damaging it without the pilot’s knowledge. As the helicopter tried to take off, it went out of control and crashed into the wreckage of the other two helicopters. The Rangers inside the helicopters suffered no major injuries, but several who leaped from the aircraft were struck by the blades. Three Rangers died, and five were seriously injured. While the rest of the helicopters hovered, the Rangers jumped and quickly secured the compound. They suffered no further casualties.

|

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,843

Likes: 13,230

|

Post by stevep on Oct 27, 2020 11:17:42 GMT

Well that does sound like a very bad case of micromanagement, especially given the losses taken and the lack of actual resistance there.

Steve

|

|

gillan1220

Fleet admiral

I've been depressed recently. Slow replies coming in the next few days.

Posts: 12,609

Likes: 11,326

|

Post by gillan1220 on Oct 27, 2020 11:20:15 GMT

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 27, 2020 14:59:50 GMT

There is a scene in the movie called Heartbreak Ridge by Clint Eastwood that duplicates that event, but as i cannot find the scene i will post this instead. |

|

lordroel

Administrator

Member is Online

Posts: 68,012

Likes: 49,410

|

Post by lordroel on Oct 28, 2020 3:51:06 GMT

DAY 4 of Operation Urgent Fury, Friday, October 28th 1983Political eventsUN failed to pass motion which deeply deplored the invasion of Grenada only because it was vetoed by the United States, one of only five countries with veto power. Combat operations (Air, Land and Sea)The collapse of any substantive resistance became apparent during operations on the fourth day. Airborne troopers spent most of the day continuing the search for any fugitive Cubans and trying to locate Hudson Austin, Bernard Coard, and other members of the revolutionary government still in hiding. Elements of Colonel Silvasy’s 2d Brigade closed on St. George’s, having swept the area between the capital and the airfield to flush out Grenadian or Cuban snipers. Near the Ross Point Hotel, the 2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry, unexpectedly ran into the marines, already occuppying the position. Absent compatible communications, neither was aware of the movements of the other, and only luck prevented a friendly fire incident. Elements of Colonel Scott’s 3rd Brigade continued their advance to the east to clear the southern portion of the island. Early in the morning, the 1st Battalion, 505th Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. George A. Crocker, moved onto the Lance aux Épines Peninsula looking for more missing medical school students. They found some two hundred Americans, mainly students, as well as a few other foreign nationals needing to be transported out of the country. Black Hawks from the 82nd Aviation Battalion flew the rescued group to the airfield where they boarded C–141s for the United States. A total of 581 American students and over 100 other foreign nationals were evacuated during the course of the operation. As combat wound down, fears of U.S. planners that the Cubans or Grenadians were planning a prolonged resistance to the U.S. invasion or even a guerrilla war evaporated. Although elements of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) were alerted for a possible mission to reinforce the two 82d Airborne Division brigades already on the island, that was soon canceled. The two Ranger battalions were finally withdrawn back to the airfield beginning at 1400 and completed their departure from the island early the next morning. By the end of the day on the twenty-eighth, General Trobaugh realized that a small peacekeeping force would suffice to secure the new interim government led by Sir Paul Scoon. Photo: A Soviet-made BRDM-2 amphibious armored scout car captured during Operation Urgent Fury.

|

|